Men diagnosed with prostate cancer are placed in a unique and unenviable position in that they are usually asked to decide themselves how they want it treated. Patients understandably want the best treatment and for many this equates to having the latest technique. Many conclude that their best option lies with either radiotherapy or surgery, and so I wanted to write this article to help those considering such a choice to make the best decision.

Patients and their relatives usually read the written information provided to them after the diagnosis or look at the web pages of an organisation such as Macmillan, the Prostate Cancer Support Organisation (PCaSO) or Prostate Cancer UK. These will list the options, common side-effects (there are always some) and sometimes the pros and cons of each treatment. The problem is that none of these websites – and seemingly few urologists – will come off the fence and tell patients that although they have several options, these options are not usually equal. Additionally, the range of options and the results of available treatments will depend on where they live and who is treating them.

To patients initially, the appeal of radiotherapy compared to surgery seems obvious, as it is less invasive than a prostatectomy (surgery to remove the prostate entirely). First of all, it’s important to explain what radiotherapy is, as well as distinguish between the different types of radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy for prostate cancer

Generally speaking, prostate cancer radiotherapy works by using focussed energy beams to cause tissue damage to the cancerous tumours in the prostate, with the expectation is that healthy cells will recover and cancerous cells will die. Prostate radiotherapy comes in many forms but the simplest classification divides radiotherapy into two broad categories.

Externally delivered: This method delivers energy into the prostate to kill the tumours from the outside, and can come in the form of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT) or the Cyberknife machine.

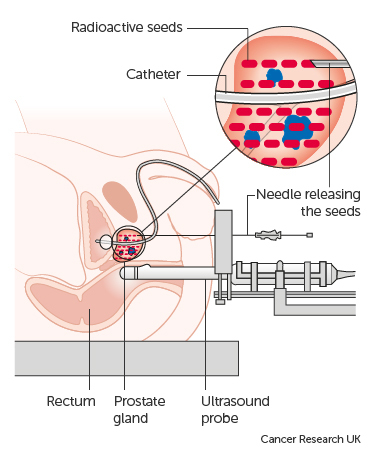

Internally delivered: Brachytherapy takes an internal approach, delivering energy from within to kill the tumours by implanting the prostate with around 100 radioactive seeds, each about the size of a grain of rice. Over time, they release energy up until about 9 months, when the energy emitted gradually stops. It is generally suitable for:

- Those with stage T1 or T2 cancer

- Those with localised prostate cancer (i.e. the cancer is contained within the prostate gland and has not spread)

- Those with a low PSA reading of below 20

The procedure is usually performed under general anaesthetic, just like prostate cancer surgery. You don’t have to spend the night in hospital.

Prostate cancer treatment method for brachytherapy (image from Cancer Research UK)

The effects on the prostate and surrounding tissues are very similar to the external method however, because the laws of physics governing radiotherapy are the same, whatever its source. Brachytherapy can also be combined with external radiotherapy and/or hormonal therapy for more aggressive and/or larger tumours, but side effects can then increase such as more urinary and bowel symptoms (frequency, urgency, urge incontinence, bleeding), and sexual symptoms such as impotence.

Success rates: While patients can experience a short-term cure with radiotherapy techniques such as brachytherapy, unfortunately it is usually much less successful compared to surgery in preventing future recurrence of prostate cancer – because the prostate remains in the body. Evidence seems to indicate that if cancer recurs again in the patient after radiotherapy, it is likely to recur in the prostate again: one study has shown that 81% of recurrent cancer following radiotherapy recurs within the prostate. This adds weight to suspicions that radiotherapy is not a long-term cure for prostate cancer.

Additionally, a systematic review of prostate brachytherapy trials published in 2011 concluded that ‘current evidence is insufficient to allow a definitive conclusion about overall survival. Randomised trials focusing on long-term survival are needed to clarify the relevance of brachytherapy in patients with localised prostate cancer’. This opinion is unlikely to change because patients who choose to undergo brachytherapy will not agree to have surgery instead and vice versa.

Surgery as a treatment for prostate cancer

Surgery for prostate cancer involves removing the prostate entirely, and is known as a prostatectomy. It has undergone a revolution in the past 20 years and is now commonly done using a technique known as keyhole surgery (or laparoscopy), where small incisions are made in the lower torso and cameras inserted to give the surgeon a complete view as he or she operates. Like brachytherapy, it is carried out under general anaesthetic.

Professor Christopher Eden conducting a prostatectomy

Compared to brachytherapy (and other forms of radiotherapy), the key features and advantages of keyhole surgery are:

- Growing evidence that surgery (and particularly robotic surgery) is better in terms of long-term cancer survival rates. Not only this, but evidence indicates that functional (bladder and sexual) outcomes are improved for patients, especially when brachytherapy is combined with external radiotherapy techniques and consequently more side effects are experienced.

- The prostate is removed entirely. This gives our testing process much more clarity as the PSA reading (an indicator of prostate cancer) falls to zero within 3-4 weeks after surgery – giving us a very clear indication of your health after treatment. Patients too enjoy the certainty of knowing that the cancerous prostate has been completely removed.

- Existing urinary symptoms are solved too. Removing the prostate treats existing urinary symptoms (such as frequency and urgency) if these are present due to enlargement of the prostate.

- Patients can still have radiotherapy after surgery, but it is usually not possible to perform surgery on a patient that has previously had radiotherapy. Due to the prostate gland remaining in the body after radiotherapy and PSA therefore still being generated, there is a delay in recognising any prostate cancer recurrence when we look at a patient’s PSA levels. Consequently, patients who need surgery after radiotherapy has failed are therefore older and their cancers are usually larger, making a successful outcome less likely. Furthermore, the surgery itself is more difficult as the tissues around the prostate are no longer normal, so complication rates are higher and patient results are poorer. Essentially, having surgery first still allows for radiotherapy as a backup treatment, but typically not vice versa.

- The better treatment for younger men. Surgery is the default treatment for younger men because of the importance of being able to interpret PSA test results with clarity, being able to use the fall-back option of radiotherapy in the future and due to the increased risk of pelvic cancers (rectum and bladder) caused by radiation treatment that can emerge 20 years after treatment. Surgery in younger men is also associated with much better continence and potency, so although this group of men are the ones most concerned about the risks of post-operative incontinence and impotence, in the hands of an experienced surgeon they are likely to have neither.

Finally, it is important to note that not all surgery is, and not all surgeons are, created equal. The importance of choosing an experienced surgeon – i.e. one who does at least 100 cases a year – cannot be over-emphasised in terms of patients achieving a successful result and becoming free of prostate cancer. It is well established that there is a direct relationship between the number of cases per year that a surgeon performs and his or her results for complex procedures such as keyhole prostate cancer surgery.

I hope this article has shed some light on the options patients have when choosing a treatment for their prostate cancer. If you do require more information or would like to book a consultation to discuss surgery, then please contact one of my team.