INFORMATION ABOUT PROSTATE CANCER

Prostate Cancer Guide

- Author’s Introduction

- Introduction to prostate cancer

- What is the prostate?

- What is prostate cancer?

- What are the causes of prostate cancer and what can I do to prevent it?

- Symptoms of prostate cancer

- Testing for Prostate Cancer

- How do I get tested initially?

- PSA test

- MRI Scan

- Biopsy

- Treatments

- Active surveillance

- Radiotherapy

- Brachytherapy

- Surgery

Author’s Introduction

In all our years as prostate cancer surgeons, one thing that has been fairly constant is a patient’s need for information. From the moment they suspect something is wrong, they try to soak up as much knowledge as they can from a variety of sources. Yet there is much to confuse the newcomer, and little in the way of advice directly from the doctors and surgeons themselves – those on the front lines, fighting against prostate cancer every day. In writing this Guide, we’ve also brought in advice from GPs, oncologists and past patients who have experienced each treatment option so you receive a balanced overview from others who have dealt with prostate cancer cases first-hand.

This guide has been created to concentrate our learnings over the last two decades into one easily-understood, jargon-free resource for patients, and to help all men understand prostate cancer better. For the better we all understand prostate cancer, the better we can make well-informed decisions on how to treat it.

Whether you’re just curious about the disease or deciding how to treat your own condition, this guide has been designed to be approachable and helpful: a comforting resource you can rely on to answer your most pressing questions. From initial suspicion to getting tested, receiving a diagnosis, undergoing treatment and then a final prognosis, we hope the guidance contained within will help you each step of the way.

To your continued good health,

Professor Christopher Eden

Introduction to prostate cancer

This chapter includes:

- What is the prostate?

- What is prostate cancer?

- What are the causes of prostate cancer and what can I do to prevent it?

- Symptoms of prostate cancer

What is the prostate?

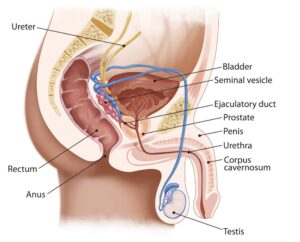

The prostate is a small, golf ball-sized gland that is a key part of the reproductive system. As you can see in the diagram below, the prostate sits below the bladder and in front of the rectum. It surrounds part of the urethra, the tube that carries urine from the bladder to the tip of the penis. When things go wrong in the prostate, because of its location, patients can sometimes suffer from issues with urination, which may be a symptom of prostate cancer. But we’ll come to symptoms later.

The main function of the prostate is to add fluid that nourishes the sperm produced by the testicles, making semen. This is stored in the seminal vesicles, ready for release during ejaculation.

Prostate diagram in human body

What is prostate cancer?

Prostate cancer is the most common form of cancer in men. It’s an abnormal and uncontrolled growth of cells within your prostate gland. This happens as a result of mutation (random changes) of healthy cells, leading to cancerous cells developing. These cancerous cells form larger clumps known as tumours. This is a problem because a growing tumour can destroy the normal cells around the tumour and spread to damage the body’s other healthy tissues.

Prostate cancer does not always pose a threat to health but certainly can, depending on its aggressiveness (or ‘grade’). In the UK alone, some 40,000 cases are diagnosed each year, with 99% of these cases in men aged over 50. 10,000 men a year die of prostate cancer, which equates to roughly one man every hour. Apart from grade, the other measure of the seriousness a prostate cancer is its ‘stage’ – or the extent to which it has spread in the prostate gland. These two measures – grade and stage – have a large influence on how we decide to treat it, as some prostate cancers may be slow-growing. Other prostate cancers may be aggressive, requiring prompt medical treatment.

What are the causes of prostate cancer and what can I do to prevent it?

Like many cancers, how tumours in the prostate form and develop is still largely unknown. However, we do know that they can be influenced by a few factors.

- Family history: if a first-degree relative (e.g. your father or brother) has had prostate cancer, this increases the risk of you developing it too by 2-3 times. The more family members affected, even if they are not first-degree the higher the risk of you developing the disease.

- Age: as you age, the risk increases. Over 99% of cases of prostate cancer are in men aged 50 and over.

- Ethnicity: for reasons yet unknown, black men are more likely to get prostate cancer than any other ethnicity, while those of Asian origin are less likely than average.

- Obesity, exercise and diet: Prostate cancer is commoner in men who are overweight and who take little exercise. Dietary factors that increase the risk of prostate cancer include a high intake of saturated fat (present in red meat and dairy products) and a low intake of fruit and vegetables, which contain natural antioxidants and anti-cancer compounds.

If you are looking to prevent prostate cancer, unfortunately there is no single cast-iron prevention available. Having said that, we recommend that men looking to minimise the chances:

- exercise 3 times a week for at least 20 minutes.

- control their weight.

- eat red meat no more than 3 times a week.

- eat and drink dairy products in moderation.

- eat plenty of fruit and vegetables, especially tomatoes which are rich in lycopene.

Symptoms of prostate cancer

Most men with prostate cancer have no symptoms of it. Instead, men often seek advice or help from their GP because of symptoms associated with the enlargement of their prostate. This may be caused by prostate cancer, but you should be aware that there are other conditions such as prostatitis which cause an enlarged prostate.

An enlarged prostate could result in:

- A need to urinate frequently, especially at night.

- Weak or interrupted flow of urine.

- Difficulty starting urination or holding back urine.

- A painful or burning sensation when urinating.

However, symptoms that are more likely to point towards prostate cancer include:

- Difficulty in having an erection.

- Painful ejaculation.

- Blood in urine or semen.

If you experience any of the above then you should make an appointment with your GP to run tests including having your PSA (prostate specific antigen) checked. Even if you do not experience any symptoms but are still worried, perhaps because a close relative has also had prostate cancer, then you should still be checked anyway above the age of 40.

Testing for prostate cancer

This chapter includes:

- How do I get tested initially?

- PSA test

- MRI Scan

- Biopsy

How do I get tested initially?

The first step is to make an appointment with your GP. They will discuss your symptoms, and enquire about your lifestyle and any medication you are taking to come to a decision about whether you should undergo further tests, such as a PSA test. If you wanted to, you could also skip the GP stage and arrange an inexpensive PSA test through a private clinic.

Know your rights!

Under the NHS Prostate Cancer Risk Management Programme you can request a PSA test from your GP once you are over the age of 50.

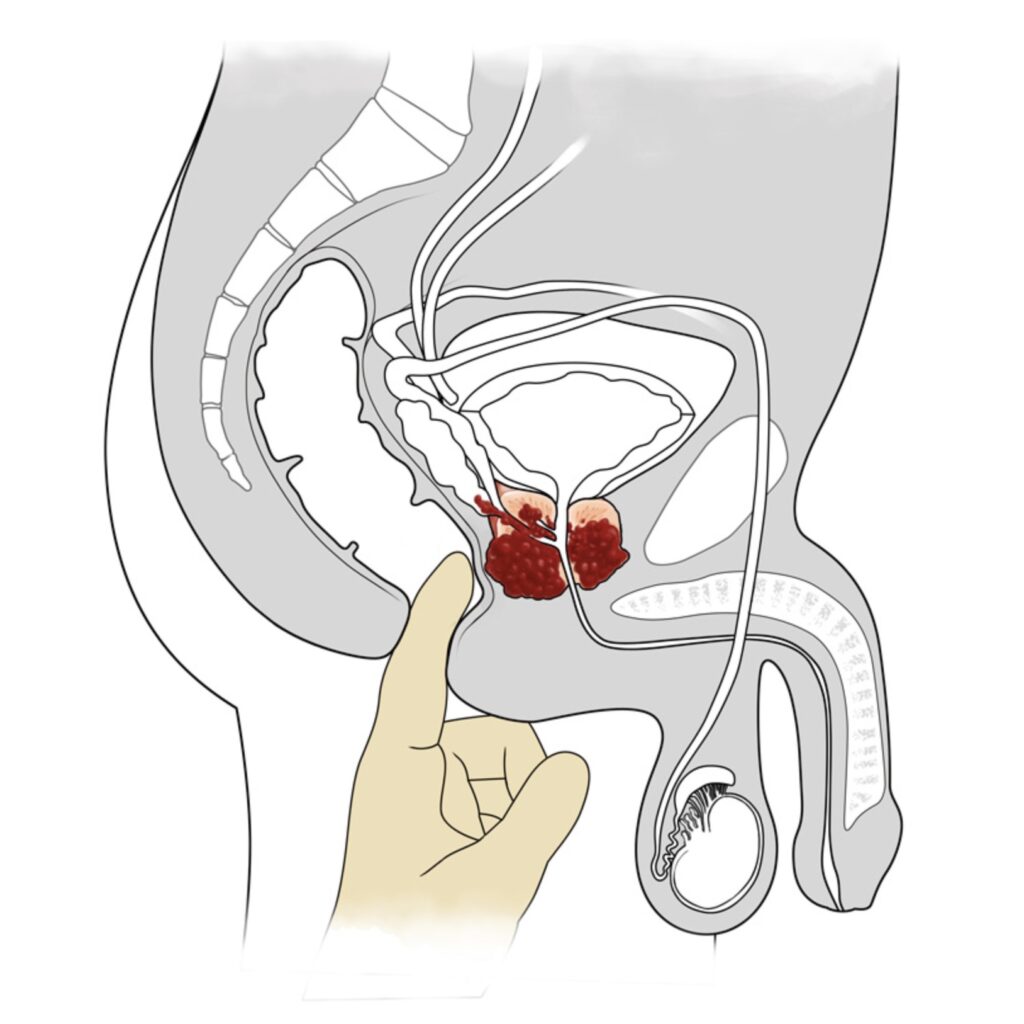

Your GP may also conduct a rectal examination (known as a digital rectal exam, or DRE) to feel your prostate with a finger. If it is firm, hard to the touch or otherwise irregular this needs investigation to investigate the possibility of cancer.

Prostate digital rectal exam diagram

Interview with a GP

Dr. Philip Whitehead has been on both sides of the patient/doctor divide: as a GP, he has tested, referred and supported men with prostate cancer for 30 years while in 2009, he was himself diagnosed with prostate cancer before undergoing a radical prostatectomy. He shares with us his insights into the process, and importantly what patients should ask of their GP.

How has being a prostate cancer survivor has changed your view of how GPs should approach the disease?

In my early sixties, I had mild symptoms of benign prostate enlargement with reduced stream as well as nocturia (having to frequently get up during the night to urinate). I went to my GP for a consultation, and a digital rectal examination showed prostate enlargement and a PSA test showed a level that was marginally above the normal range for my age. My GP suggested repeating the test after three months, and this showed a further rise. He referred me to a urologist but did not feel it merited a two week referral, and I was seen some months later by Professor Eden.

GPs are in a difficult situation when a patient presents with symptoms of an enlarged prostate, because this could be simply benign prostate enlargement, or it could be caused by cancer. It requires awareness of how the PSA level can change over time, and caution when interpreting a single reading. When cancer is a possibility, referral under the two week rule is required.

Having gone through successful treatment, what do you know now that you wish you had known before the diagnosis?

I would say that the most important things for a patient to know about are:

- The various treatment options of active surveillance, brachytherapy, targeted radiotherapy, radical prostatectomy (whether laparoscopic or robotic), medication;

- Your Gleason score determines the best treatment option for you

- The complications – early, medium and long term – of each treatment

- The importance of the 3Ps in follow up as a measure of success – namely PSA, potency and peeing

- Impotence is not inevitable, although a change in sexual experience and ejaculation will be apparent if radical prostatectomy has been undertaken

- Flaccid penis length may change but erect length would be unchanged

- Tadalafil (or similar) reduces incidence of erectile dysfunction when taken during the early period after the operation, as well as later.

What should your GP know about prostate cancer?

- They should have an up to date knowledge of prostate carcinoma, NICE guidelines, higher incidence in Afro-Caribbean men and those with close family history, Gleason scoring, treatment options

- They should be aware that normal findings from a digital rectal exam do not exclude malignancy, and that further testing may be required

- They should have knowledge of (age-adjusted) normal PSA values, and the significance of an elevated reading

- They should be aware of the need for serial PSA tests (where a series of PSA tests are conducted and the results monitored over time) if a patient’s PSA results are borderline worrisome, while bearing in mind how PSA levels can fluctuate

- They should know about the two week rule – that you should be referred to a urologist within 2 weeks if malignancy is a possibility.

What is the role of the GP in all of this (not only before testing, but after treatment too)?

- They should offer a PSA test in older patients (even if they do not show any symptoms) if they are worried – especially if the patient has Afro-Caribbean heritage or close family history of prostate cancer

- Include PSA test as well as fasting glucose and cholesterol during Well Man screening

- Arrange PSA test if symptomatic

- Inform patient of low risk of malignancy (~25%), even if they have an abnormal PSA result

- If referral is required, advise the patient of the possibility of a biopsy and further procedures to determine the stage of the cancer

- If cancer is found, discuss treatment options and outcomes, and reassure patient that impotence and urinary/faecal incontinence is not inevitable.

If the patient undergoes surgery to treat their cancer, what are the GP’s roles and responsibilities after the operation?

- They should advise the patient of the need (in the first few days after the operation) for high fluid intake, regular use of painkillers and keeping mobile to prevent blood clots

- They should arrange nursing referral for catheter care and wound management

- If a Urinary Tract Infection is suspected, it should be treated promptly with appropriate antibiotics

- Liaise with urologist regarding prescribing of Tadalafil to reduce the incidence of erectile dysfunction

- Discuss potency with patient (and perhaps partner too), and if necessary, make a referral to a suitable sexual dysfunction clinic

- Arrange regular follow up for the patients by way of PSA testing to ensure that the level is close to zero, following an agreed protocol for how frequently these tests should be conducted and what might trigger a re-referral back to the patient’s urologist in case there are signs that the prostate cancer has not been completely eradicated.

PSA test

The first step in testing for prostate cancer is taking a blood test to check your level of PSA (prostate specific antigen). It’s a substance that is produced by your prostate normally and is detectable in the blood of all men. However, a number of factors are known to increase it:

- increasing age;

- increasing size of prostate;

- urinary infection;

- an obstructed bladder due to benign enlargement of the prostate;

- prostate injury, such as a biopsy or a long and bumpy bike ride;

- ejaculation;

- prostate cancer.

Although an elevated PSA level increases the risk of prostate cancer, it is important to know that PSA is not a test for prostate cancer specifically – it is only an indicator. Its main use is to identify men who need further investigation. Having said this, the largest prostate screening trial ever conducted (the European Randomised Screening Study for Prostate Cancer) found it to be a very reliable indicator. You can have prostate cancer with a normal PSA reading – so there are other tests we can perform later if necessary. But it’s a good first step.

If your GP recommends a PSA test (you can also demand one if they refuse), then you will be able to have it performed at your surgery. Your results will take around 1-2 weeks to be available, and like other test results, you can get them by telephoning the surgery or scheduling a follow-up appointment.

If you would rather be seen urgently or are encountering difficulties getting a PSA test with your GP, it may be worth arranging a PSA blood test at a private clinic. Many offer an appointment on the same day, with results available within 3 working days. For example, the Surrey Park Clinic in Guildford, Surrey charges around £75 for a PSA test.

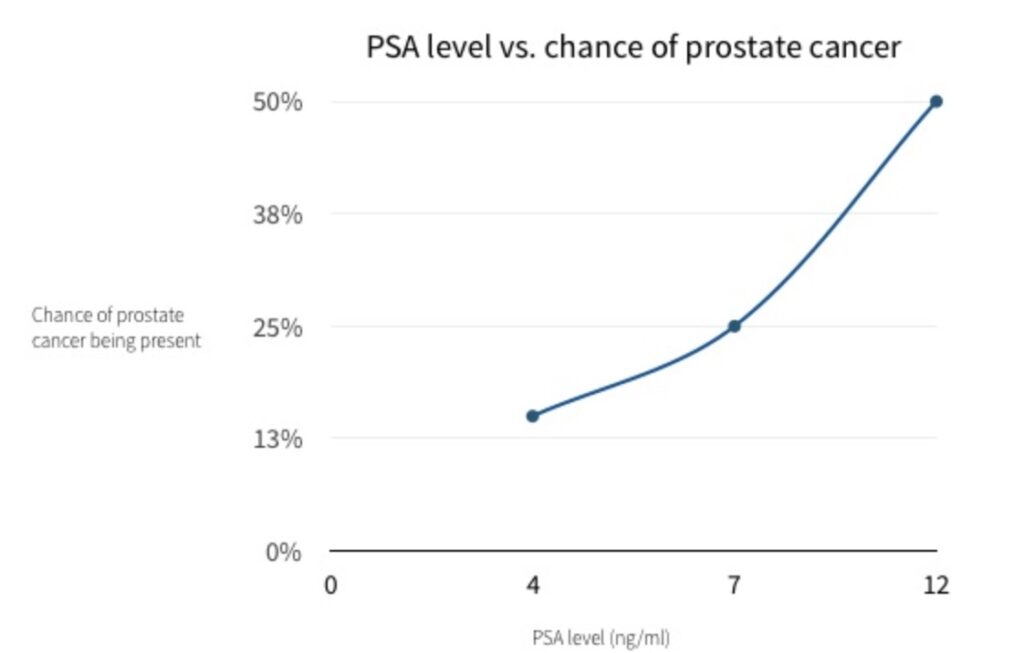

What your results mean:

- As the amount of PSA that a prostate produces normally rises with age the NHS has produced the following age-specific normal ranges: 0-2.5 if 40-49, 0-3.5 if 50-59 and 0-4.5 above the age of 60.

- The units of PSA are nanograms (ng) per millilitre (ml) of blood. As stated above, an elevated PSA level does not definitively mean that you have prostate cancer.

- Equally, a normal PSA does not mean that you don’t have prostate cancer: 20% of men with prostate cancer have a normal PSA. This why a rectal examination is important.

- If your PSA is 4 – 10, then your likelihood of having prostate cancer rises to around 25%.

- If it is over 10 then your likelihood is over 50%, with the likelihood increasing the higher the PSA level is.

PSA results chart – likelihood of prostate cancer

It varies by GP, but if your PSA test result is above your age-adjusted normal level then you should be referred to a urologist for further testing (such as an MRI scan and/or a biopsy) to determine if you really do have prostate cancer and if you do, to additionally determine the stage of the prostate cancer and what the best treatment is.

Remember, you can choose which urologist you want to consult with and possibly treat you and your choice is not just limited to your local urologist. For example, you may want to see your local urologist for convenience, but you may want to do some research about which urologists specialise in prostate cancer and then travel further afield to see them. This is very common in some countries, like the US, and you shouldn’t feel awkward about doing this. Alternatively, you can make a private appointment directly with a urologist rather than going through the NHS system. At Santis for example, we usually see 10-20 new patients every week.

MRI scan for prostate cancer

A magnetic resonance imaging scan (MRI) allows your urologist an extremely clear picture of your prostate, including any enlargement, swelling, or even if the tumours have broken out of the prostate capsule itself. It is therefore important in assessing the stage of your prostate cancer – or how far the cancer has spread within the prostate gland.

The below video explains how MRI works and what you can expect during your scan.

MRI scan for prostate cancer patients

At Santis, our normal practice is to arrange an MRI scan prior to a prostate biopsy for newly referred patients. There is growing evidence that this is important for two main reasons:

- The needles used during a biopsy puncture the prostate and can cause minor bleeding. This bleeding can show up as ‘biopsy artefacts’ on the final MRI image, reducing the clarity of the image of your prostate.

- If an abnormality is seen on MRI scanning before a biopsy, it can be specifically targeted during the biopsy, increasing the detection rate for prostate cancer (if cancer is present).

Abnormalities seen within the prostate are classified using the PIRADS (Prostate Imaging Reporting And Data System) system with a score of 1 indicating the lowest suspicion of prostate cancer and 5 indicating the highest level of suspicion. PIRADS scores of 3 or more usually trigger a prostate biopsy if the prostate feels normal on digital rectal examination. If the DRE is abnormal then the prostate should always be biopsied.

Typically it takes around 2 weeks for an MRI scan to be arranged on the NHS, and then a further 2 weeks for the results to be available.

Your MRI scan will provide you with the stage of your prostate cancer

In patients who are subsequently diagnosed with prostate cancer, the MRI scan provides the stage of the cancer, with the letter T used to indicate the stage of the tumour. Stage means how far the cancer has spread. Although the stage can be assessed by digital rectal examination, it is more accurately assessed by an MRI scan.

Stage T1

T1

T1 tumours are too small to be seen on scans, or felt during examination of the prostate. They may be discovered during a biopsy examination though. T1 tumours are not very serious.

Stage T2

T2 tumours are subdivided into three stages, T2a, T2b and T2c. Together they are commonly called localised prostate cancer. This is where the cancer is completely contained within the prostate. T2 tumours are more serious, but can be effectively treated.

T2a

T2a tumours are where tumours are found in only half of one of the two lobes that make up the prostate gland.

T2b

T2b tumours are where tumours are found in more than half of one of the two lobes.

T2c

T2c tumours are where tumours are found in both lobes, but the overall cancer is still contained within the prostate gland.

Stage T3

T3 tumours are subdivided into two stages, T3a and T3b. Put together, they are commonly called locally advanced prostate cancer. This is where the cancer has broken through the outer covering of the prostate, but has not spread to other organs. T3 tumours are fairly serious.

T3a

T3a tumours are where tumours have only broken through the outer covering of the prostate.

T3b

T3b tumours are where tumours have broken through the outer covering of the prostate and have also spread to the seminal vesicles.

Stage T4

T4 tumours have spread to other organs nearby, such as the rectum, bladder. It is also called metastatic prostate cancer. This is the most serious form of prostate cancer.

Whether you require treatment or not – as well as which treatment is most effective – is heavily dependent on the stage and grade of your prostate cancer.

T1 and lower grade prostate cancers might not require any treatment at all, while T2b and above is usually deemed as carrying a higher risk by urologists, and so usually require treatment – either radiotherapy, brachytherapy or surgery to remove the prostate itself.

Introduction to biopsy

The definition of a biopsy is ‘an examination of tissue to discover the presence, cause, or extent of a disease’. A prostate biopsy will give you a certain diagnosis as to whether you do have prostate cancer. It is the most accurate test available for prostate cancer.

It is the urologist, rather than your GP, who decides whether you need a prostate biopsy taking into account your age, PSA, DRE and MRI scan results. In the NHS, the usual wait time for a biopsy is between 2-6 weeks, with results available after 2 weeks.

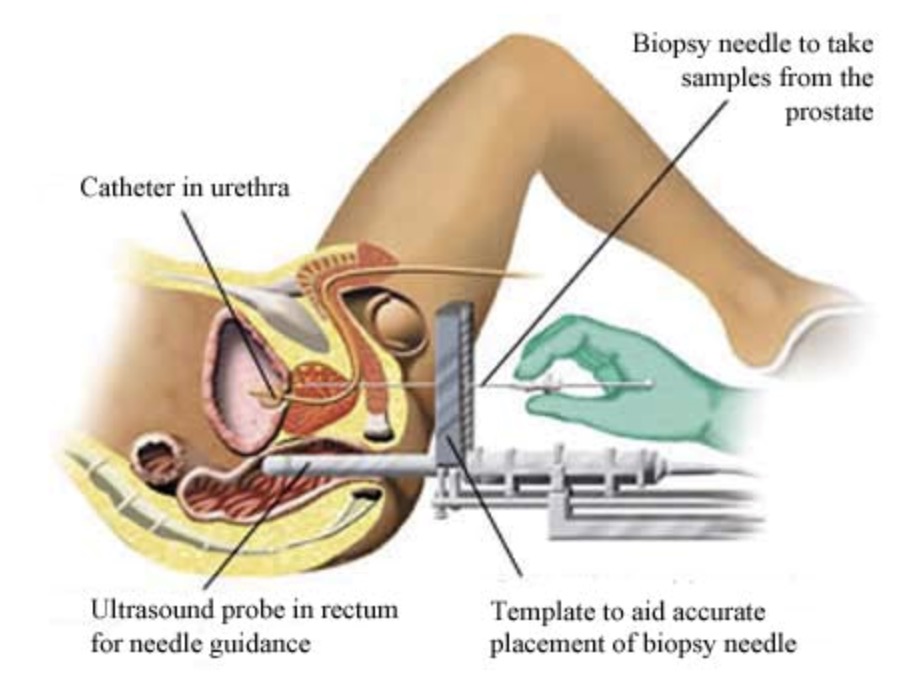

Procedure

Depending on the method of prostate biopsy the procedure will take 10-60 minutes. You will either:

- have your prostate and rectum numbed with a local anaesthetic and biopsies then taken through the rectal wall (transrectal biopsy), or

- have a general anaesthetic as a day case patients and have the biopsies taken through the skin behind the scrotum and in front of the anus (transperineal biopsy). This gives better access to all parts of the prostate and the use of a biopsy grid allows the biopsy needle to be placed with great accuracy.

With both techniques an ultrasound probe is used to measure the size of the prostate and to guide the biopsy needles into the prostate in real time. Between 10-60 samples of tissue are taken, which are then tested microscopically in the laboratory for signs of prostate cancer.

Results

After 1-2 weeks the results of your biopsy will be sent to your urologist in what is called a pathology report. This report will state:

- if cancer was found;

- how many biopsy cores (samples) contained cancer;

- how much cancer was present in each sample;

- the grade of the cancer in each positive core.

Gleason score

When a Pathologist diagnoses prostate cancer under a microscope they assign a Gleason score to each sample. The Gleason score expresses the grade of the cancer, or how aggressive the cancer is and how likely it is to spread.

This score is based on the microscopic appearance of the cells compared to normal prostate cells. If they are not very different, it is a low grade, or an ‘indolent’ cancer. If they are very different, it is a high grade, or an aggressive cancer.

Grade vs. stage

Note that the grade is different to the stage of your prostate cancer, which we described earlier in the MRI section of the Prostate Cancer Guide. Remember, the stage describes how far your cancer has spread. For example, you may have an aggressive prostate cancer (high grade) that has not spread very far (low stage). So we now have two measurements to describe your cancer: the grade and the stage. Together with your PSA prior to prostate biopsy this becomes important later in deciding how to treat it.

The Gleason score for your samples is assessed as follows:

1 or 2 – these are normal prostate cells

3 – fairly abnormal cells detected

4 – moderately abnormal cells

5 – highly abnormal prostate cells

The most common Gleason score out of all of your samples is taken, and then added to the second most common Gleason score out of all your samples to give you a total Gleason score out of 10. This standard method of reporting ensures that your urologist fully understands the likely behaviour history of your particular prostate cancer and so know how best to advise you.

Now that both you and your urologist have a clear idea of both the grade and the stage of your prostate cancer, you are now in a very good position to decide on how to treat it. Your urologist will talk your best options through with you as it ultimately is a personal decision, but one heavily influenced by various factors that they will explain to you.

Treatments

This chapter includes:

- Active surveillance

- Radiotherapy

- Brachytherapy

- Surgery

Introduction to active surveillance

This not a treatment as such as the prostate is not ‘treated’. Instead, it’s more of an approach to managing the disease. This may sound strange, so let us explain.

The word ‘cancer’ frightens a lot of people, and many automatically assume that it implies aggressive cancer with aggressive treatment options required. However, this is not the case for all cancers. Because many prostate cancers are slow growing and have not spread, it’s common in fact for men to outlive their prostate cancer – they may never need treatment. This is particularly the case for low grade tumours in older men and it can work well for some patients. It’s more of a wait-and-see approach and if your cancer does progress, then you can usually have it treated successfully because it is being monitored.

What it involves

Just as when you were first tested for prostate cancer, you will undergo the same tests, except with more frequency:

- PSA tests every 3-6 months with your GP and follow-ups with your urologist;

- MRI scan each year;

- repeat prostate biopsy every 2 years.

If your tests show evidence of tumour progression (rising PSA, increasing abnormality on the MRI scan or biopsies that show either an increasing amount or aggressiveness of cancer) you will be advised to stop active surveillance and have some form of definitive treatment, such as radiotherapy or surgery. This applies to approximately a third of active surveillance patients. A further third abandon active surveillance because of anxiety and the intensive surveillance protocol.

Pros

- There’s no recovery time or side effects as direct treatment is not involved;

- For self-paying private patients it is a lower cost option than radiotherapy or surgery.

Cons

- It may be stressful to know that you are living with cancer.

- You may feel anxiety when undergoing your tests, as at any time they may show that your cancer has developed further.

- There is a small chance that your cancer can develop too quickly to be able to treat it successfully.

- You are required to undergo further tests including prostate biopsy, which not all patients would find acceptable.

Radiotherapy

This section on radiotherapy was written by Richard Shaffer MRCP, FRCR, who is the Clinical Lead for Radiotherapy and Consultant Clinical Oncologist at the Royal Surrey County Hospital in Guildford.

Introduction to radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is the use of controlled, focussed X-rays to damage cancerous cells in your prostate. The aim is that the surrounding healthy cells recover whereas the cancerous cells do not. It can be used to cure localised prostate cancer i.e. where it is in the prostate and the seminal vesicles. It can also be used when it has spread to the glands in the pelvis. There are two main types of radiotherapy: externally delivered (external beam radiotherapy – which is what we are discussing here) and internally delivered, which is known as brachytherapy.

Radiotherapy is particularly useful where patients are worried about the risk of incontinence with surgery, where they are not eligible for surgery, or where they are worried about the risk of significant bladder irritation with brachytherapy. Radiotherapy can also be used if surgery has not been successful. Patients below the age of 55 – 60 years old tend not to be treated with radiotherapy due to the small risk of radiotherapy causing a new cancer after several decades, despite curing the prostate cancer.

There is no definitive proof that any of the whole gland treatments (radiotherapy, brachytherapy, surgery) is better than another.

How is radiotherapy given?

External beam radiotherapy tends to be given as a daily treatment over a number of weeks (generally 4 – 7 weeks). Each treatment requires the patient to lie on a hard couch while a machine moves to various positions. Nothing touches the patient. The process is entirely painless, and does not involve needles or an anaesthetic. Each treatment takes ten minutes per day. It does not make the patient feel drowsy or dizzy, and patients can drive and continue to work through the course of treatment.

The X-rays are aimed very exactly at the prostate gland, using a dose-shaping technique (IMRT), and a guidance technique (IGRT), to ensure that the prostate is targeted exactly each day, and the other organs (rectum and bladder) are not treated with too high a dose of radiation.

Radiotherapy tends to be given with a course of hormone treatment that blocks testosterone (either tablets or injections), as this has been shown to make it more effective.

After radiotherapy

After your course has finished, you will have a PSA test and a check up between 3 weeks and 6 months to see how your prostate has responded. Your PSA level should begin to drop after radiation but can take several years to reach its lowest level. A stable and low PSA level indicates successful treatment.

What side-effects can you get?

During the first two weeks of treatment, there do not tend to be any side-effects, but towards the end of the treatment, some patients experience irritation of the bladder and bowel, which can cause diarrhoea, and frequency of emptying the bladder. In most people this is fairly mild and temporary, and this treatment does not cause incontinence of the bowels or bladder. However, 5 – 10% of patients have longer-terms bowel or bladder side effects.

Additionally, there is a risk of causing loss of erections in the long-term with this treatment, although often this can be treated successfully with treatments such as Viagra.

How successful is radiotherapy?

The success of any curative treatment depends on many factors, but particularly how high a risk your tumour was. Factors would include the PSA, the Gleason score, and stage (i.e. how far the tumour has spread in and around the prostate).

There has never been a robust comparison of the curative treatments. Therefore, it is important to discuss the success rate of the treatment in your own case, the impact of the process (e.g. number of hospital visits, having a general anaesthetic), as well as the side-effects that you would find most troublesome.

What treatments are available if radiotherapy is not successful?

The treatment would depend on the area in which the tumour recurs:

- If the tumour recurs in or around the prostate area then various treatments can be used to aim to cure the tumour, including surgery and HIFU (high-frequency ultrasound).

- If the tumour recurs in up to three places outside the prostate region, e.g. in the bones or the lymph glands, then a highly-focussed dose of radiotherapy called stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT, SABR) can be used to treat them.

- If neither of these types of treatments are possible, then “systemic” treatments would be offered, for instance hormone treatments or chemotherapy.

Brachytherapy

This section on brachytherapy was written by Dr. Sara Khaksar, who is a Consultant Clinical Oncologist at the St Luke’s Cancer Centre, Royal Surrey County Hospital in Guildford, Surrey. She has over a decade of experience in brachytherapy and personally performs more than 10 procedures a month.

Introduction to brachytherapy

In contrast to radiotherapy (which delivers external radiation), brachytherapy is internally delivered and does not require repeated sessions. Instead, the operation is usually performed under general anaesthetic or spinal anaesthetic, and usually requires only an overnight stay in hospital.

Internally delivered means delivering energy from within the prostate to kill the tumours. There are two types of prostate brachytherapy: Low Dose Rate (LDR) and High Dose Rate (HDR).

Low Dose Rate (LDR) Brachytherapy

What is it?

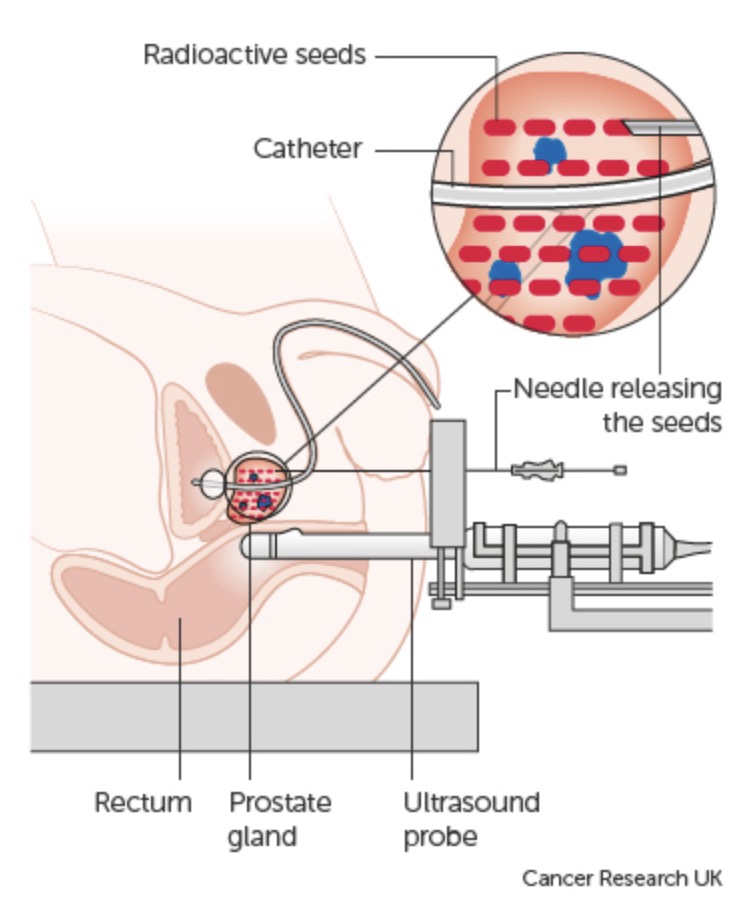

This is the insertion of radioactive ‘seeds’ of Iodine-125 directly into the prostate. The radioactive iodine is encased in titanium and looks like a rice grain. Iodine-125 emits radiation at a low rate (hence its name), so the total dose is delivered over 3 to 4 months. Beyond this period, although the seeds still emit radiation it is very low and not a cancer killing dose.

Regardless of whether you undergo LDR or HDR brachytherapy, the procedure is broadly the same. Under general or spinal anaesthetic you lie on your back and an ultrasound probe is inserted into your rectum to give the urologist and oncologist a clear view of the prostate. You are also catheterised so they can visualise your urethra (the tube you pass urine through). Needles are inserted into the prostate through the perineum (the area between the anus and your testicles), and the seeds are deposited into the prostate via these needles using the image from the ultrasound as a guide.

The procedure takes approximately 30-45 minutes. Approximately 100 seeds are implanted per person, varying according to the size of the prostate. As the seeds are implanted directly into the prostate, a high dose of radiotherapy (higher than can be given with external beam radiotherapy) can be delivered to kill the cancer, whilst sparing the surrounding bladder and rectum.

Prostate cancer treatment method for brachytherapy

A CT (computerised tomography) or MRI scan is performed either on the day of the procedure or 4-6 weeks later to check that the seeds are well-positioned in the prostate. You are seen initially 6 weeks after the procedure to ensure any side effects are settling, and thereafter seen every 6 months for 2 years and then yearly to 5 years for PSA tests. Your PSA should drop after brachytherapy and can take a number of years to reach its lowest level. A low and stable PSA indicates successful treatment.

Who is suitable?

LDR brachytherapy can be used on its own (known as “monotherapy”) or in combination with hormones or hormones and external radiotherapy. For monotherapy, the cancer must be localised to the prostate with little risk that microscopic cells have spread beyond the gland. If this risk is greater, then combination treatment may be advised to ensure the maximum chance of cure.

Patients must also have minimal urinary symptoms. The main side effect of brachytherapy is a temporary worsening of urinary symptoms due to swelling of the gland which narrows the urethra (the tube down which urine flows from the bladder). The symptoms may include an increase in urinary frequency (both day and night), urinary urgency and dysuria (stinging sensation when passing urine). Patients with significant pre-existing symptoms can find this increase troublesome and run the risk of not being able to pass urine, requiring the need to self-catheterise temporarily until the swelling reduces.

What are the side effects of LDR brachytherapy?

Most men return to usual activities within days. An increase in urinary symptoms as described is expected. In the majority of patients the increase is manageable, and settles over the 3-12 months after treatment. Potency can be affected, but when used as monotherapy in patients with good pre-existing erectile function, 70%-80% of men remain potent with or without the aid of medications such as Viagra. Rectal side effects are usually mild.

What about radiation protection?

For the first two months after the insertion of the seeds it is advised not to sit next to children or pregnant women for more than a few minutes; however they may be in the same room. It is safe to share a bed with your spouse and sexual relations can be resumed within a month.

How effective is it?

LDR brachytherapy is a very effective treatment both as monotherapy, or as part of combination therapy. It is as effective as other recognised treatments, which include surgery and external beam radiation.

High Dose Rate (HDR) Brachytherapy

HDR brachytherapy is similar to LDR brachytherapy in that the two procedures share the same technique. However the radioactive source used for HDR is Iridium-192 and this emits radiation at a higher rate than the iodine -125 used for LDR and as such releases the equivalent radiation dose in a few minutes, compared to 3-4 months with iodine-125. Because of this, permanent seeds are not left in the prostate – they are inserted into the prostate and then removed after a few seconds or minutes.

Needles are again placed into the prostate via the perineum, but the difference is that the needles are attached to flexible tubes down which the radioactive source (the “seed”) travels, one at a time. The source stays in a number of positions within each needle for a few seconds or minutes, and then returns to its container. The operation also takes 2 to 4 hours, longer compared to LDR brachytherapy.

HDR is used in combination with hormones and external radiotherapy for localised high risk prostate cancer, and for cancer that has spread outside the capsule of the gland or into the seminal vesicles. It is not used as monotherapy (i.e. it is not used on its own). There are no radiation protection requirements as with LDR, as the radiation source is not permanent. Possible side effects are similar to LDR brachytherapy.

Surgery

Surgery is an option for most stages and grades of prostate cancer, including localised and locally-advanced prostate cancer. It involves removing the prostate entirely in a procedure known as a ‘radical prostatectomy’. Instinctively, many patients want to have the cancer removed from their body and surgery provides this solution for them. It is a major operation lasting 2-4 hours conducted under general anaesthetic, and patients need to be fit enough for this.

There are two types of radical prostatectomy that you should know about.

- Open surgery (also known as radical retropubic surgery) is where a single large incision is made in your stomach and the surgeon operates through that one incision.

- Keyhole (laparoscopic and robotic) surgery (also known as minimally-invasive) is where several small incisions are made in your lower abdomen and the abdomen is inflated with carbon dioxide gas. A camera, light source and instruments are then inserted through hollow tubes called ‘ports’ to allow the surgeon to operate with a brightly illuminated and magnified view of the prostate and surrounding structures.

There are about 10,000 operations using both techniques performed each year in the UK, with open and keyhole surgery split between approximately 20% and 80% respectively. The advantages of keyhole surgery over open surgery are:

- less blood loss during the operation and a lower risk of blood transfusion;

- a lower complication rate;

- a shorter recovery time;

- cancer control, continence and potency may be superior.

Robotic surgery

You have probably also heard about ‘robotic’ surgery. This is where the surgeon uses a surgical robot (called the ‘da Vinci’) to help perform your operation. The surgeon is fully in control at all times – it is not automated like a robot on a car production line, but serves to enhance the surgeon’s capabilities. The robotic hands allow for scaled and tremor-free movements, a wider range of movement than is possible with the human hand and greater visibility for the surgeon into the patient’s abdomen during the operation thanks to magnification and a 3D view. There is some evidence that robotic prostatectomy delivers better patient outcomes than other forms of prostate surgery in terms of cancer control, continence and potency but this has not been proven in a randomised controlled trial. However, in our experience many patients want the robot used as it is seen to be at the cutting-edge of surgery. In the United States for instance, up to 90% of radical prostatectomies are now performed using the da Vinci system. For more information, see our da Vinci page.

Regardless of what technique you choose, the main difference between surgery and other treatments is that the outcome of your treatment is highly dependent on the skill and experience of your surgeon. It’s all concentrated in the hands of one person, so it’s vital you are happy with their results on previous patients and competence.

What’s involved

A radical prostatectomy is a complex operation that requires several weeks of recovery as your body heals, and patients must be fit enough to undergo it. It is conducted under general anaesthetic, so the patient is asleep for the entire duration. Six small incisions are made in the lower abdomen, and carbon dioxide is pumped in to allow the surgeon more room to operate. Cameras are inserted to give the surgeon a clear view of the prostate as he operates, removing the prostate from the nerves and arteries that surround it.

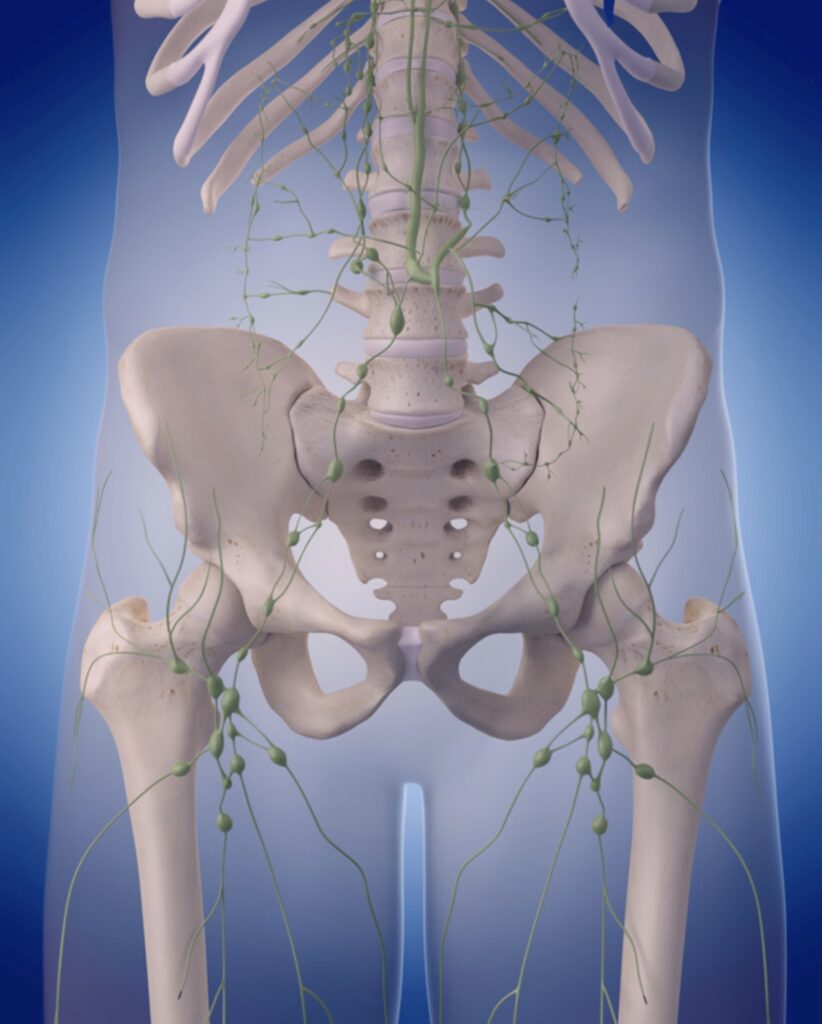

Most patients will need to have the pelvic lymph nodes removed as well. These are structures that filter infection and cancer from the fluid returning from the tissues into the circulation. You have several hundred of these structures in your body and if some are removed then the fluid simply finds another channel to flow through to return to the circulation. It is useful for them to be removed and analysed to determine the true extent of your cancer (known as ‘completing the staging’), but the main reason for their removal is that it increases the probability of a full cure.

The lymph nodes and lymphatic system around the pelvis

Once the prostate has been freed it is placed intact into an impermeable plastic bag inside your abdomen to be retrieved at the end of the procedure. This is done so the cancerous cells do not touch healthy tissue. The two structures either side of it (the bladder and the urethra) are then connected using stitches and a catheter (a soft plastic tube) is inserted in the urethra and through the join. This is left in place for 2 weeks until the join has healed. All internal and external stitches dissolve after a few weeks.

After the operation

After the operation, you will wake up in hospital and spend 2-3 days there resting. You will have a catheter inserted into your penis to allow urine to drain from your bladder, which will be in place for 2 weeks. You could expect to drive after 7-10 days and be doing 90% of what you were doing physically before the operation by 3 weeks after surgery. You will be seen again as an outpatient 4 weeks after surgery to discuss the pathology lab report on your prostate and lymph nodes and your progress. You will then have your PSA checked every three months for the first year after surgery, every 6 months for the next 4 years and once a year thereafter.

Read a patient’s experience

Dan Zeller is the US blogger behind Dan’s Journey, a journal he started back in 2010 that chronicles his experience of prostate cancer. Dan eventually chose surgery, and he shares his reasoning with us below.

“It was actually a DRE that got the ball rolling for me. I went to the doctor to have an aching hip checked out, and she noted that it had been a while (3 years) since we last checked my prostate. She did a DRE, felt a mass, ordered the PSA, and when it came back at 5.0, sent me off to the urologist for a biopsy.

The urologist took 20 tissue samples (high, if you ask me), and 11 came back positive with cancer. I was 52 years old when I was diagnosed, and I am notoriously known for researching before making a decision – even if it’s something as simple as a television.

One of the best resources that I came across to educate me about my options was “Dr. Patrick Walsh’s Guide to Surviving Prostate Cancer.” While I did explore other options, it became clear to me that surgery would be my best choice.

My thought process was that, by having surgery first, I would have radiation and hormone therapies available as salvage treatments if the cancer remained after the surgery. If I had had radiation first, the surgery would no longer be an option, and I would have one less “tool” available to beat the cancer. And, at the age of 52, I wanted as many options available to me as Plan B, Plan C, Plan D… It was that simple.”

Potency and continence

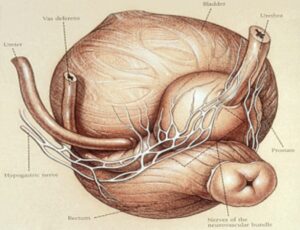

Removing the prostate is a delicate operation that requires it to be disconnected from the surrounding rectum, bladder, nerves (that control erections), veins and the urethra. While rare, damage to these areas is possible during surgery. Men in particular worry about impotence after surgery (being unable to get an erection), so I want to address this here.

Impotence is caused by damage to one or more of the two nerve ‘bundles’ that surround the prostate. In some cases, the cancer may have spread to the nerves or very close to them and so they must be removed as well to ensure the cancer is cured. But if they don’t have to be removed, then it comes down to the surgeon’s skill in handling the nerves during the operation, which as known as ‘nerve sparing’.

Prostate nerve bundle

In other words, if your nerves are not cancerous, then impotence can be avoided. The same goes for damage to your bladder, urethra and rectum. It can all be avoided in experienced hands.

Because of this, when selecting a surgeon (as is your right to do so, including in the NHS) be sure to find out how many operations they do each year, as it has been shown that patients who choose a high-volume surgeon (someone performing 100 or more operations in a year) are likely to have a better outcome in cancer control, continence and potency than if they choose a low-volume surgeon. The national average in the UK for 2014 was 31 cases per surgeon per year.

At Santis, we are able to offer nerve sparing to around 80% of our patients, and 87% of our patients who had normal erections before surgery and who had both nerves preserved continued to do so after surgery. So the fear of impotence, while understandable, is not borne out by real patient results.

Pros

- Certainty – following the operation, your prostate is removed and sent for analysis to determine the final stage and grade of the cancer. Some patients find that their final stage and grade are actually better or (more frequently) worse than predicted by the biopsy, allowing for an accurate estimation of prognosis.

- A target PSA – your PSA also falls to zero as the prostate is removed, allowing your urologist to definitively and conclusively inform you of your outcome each time you have a blood test. With radiotherapy there is no target PSA so the outcome remains unclear, often for many years.

- Avoiding radiotherapy-induced bladder and rectal cancers – although it must be stressed that while the risk is very low, it can happen to radiotherapy patients.

- Backup options – if surgery cannot control the disease, then you still have the backup options of radiotherapy and hormone therapy in reserve should you need to use them after surgery.

Cons

- You will no longer be able to ejaculate – your prostate produces seminal fluid and as your prostate is removed entirely, this will no longer be produced. Remember that you can still achieve orgasms and often erections too, so most patients do continue to have a fulfilling sex life.

- There is the risk of impotence, incontinence and bowel problems caused by surgery, although as explained above these can be minimised with an experienced surgeon.